St. John’s Law Seminar Students Explore the History and Legacy of Lynching in America

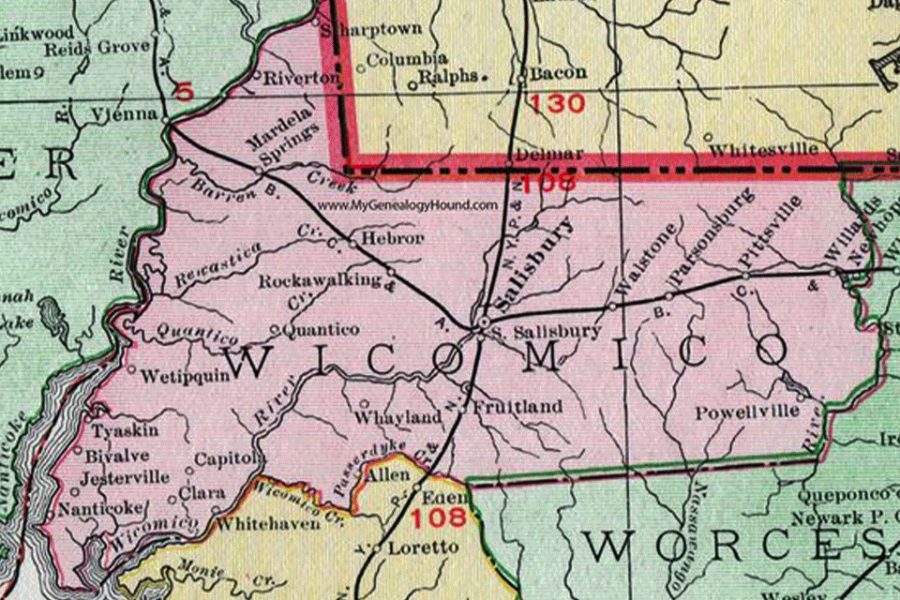

On Friday, December 4, 1931, at 8:05 p.m., 23-year-old Matthew Williams was lynched in front of hundreds of onlookers gathered on the local courthouse lawn in Salisbury, Maryland. His murder was one of three racial lynchings that took place in that largest city in Maryland’s Eastern Shore region, a good distance from the more well-known and widespread incidents of racial terror in the Deep South.

In his book, The Silent Shore: The Lynching of Matthew Williams and the Politics of Racism in the Free State, Professor Charles L. Chavis, Jr., Ph.D. brings Williams’ murder out of the shadows of history and into the light of today’s racial reckoning. The perspective he offers roots in documentary evidence and taps his expert insights as the founding director of the John Mitchell, Jr. Program for History, Justice, and Race at George Mason University’s Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter School for Peace and Conflict Resolution and as vice chairman of the Maryland Lynching Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

Professor Chavis shared those insights with St. John’s Law students recently as a guest speaker in Lynching: Legal & Dispute Resolution Responses to Violence, a seminar co-taught by Professor Elayne E. Greenberg and Professor Cheryl L. Wade. Students in the course examine the history and causes of lynching in the U.S. between 1861 and 1950 and analyze how the vestiges of that domestic terrorism continue today in the criminal justice system. They also explore how lawyers can use restorative justice principles, along with their legal knowledge and other dispute resolution skills, to address the societal vestiges of lynching that are inherent in modern-day violence in its many forms.

How the past visits the present is a focal point for Professor Chavis. “When we defend justice we necessarily defend the truth; the truth about our past and the pivotal role that the law played in defining American culture, Americans’ sense of right and wrong, and, infamously, personhood,” he says, adding, “Injustices of today did not emerge in a vacuum. Rather, they were created centuries ago intentionally, nurtured and bequeathed by subsequent generations to benefit certain groups at the expense of others.”

That legacy of injustice is also clear to seminar student Gabriel Tejada ’23 as he reflects on the conversation Professor Chavis led in class. “Choosing to engage with the past is a long-term investment for the future of our nation, particularly when it comes to healing community-wide wounds that transcend generations, which include lynching and state-sanctioned violence,” Tejada observes. “Lynchings went beyond the visceral execution of people and killed black prosperity and progress. Lynching and racial segregation has had an immeasurable intergenerational effect. Our history is the context for today.”

Professor Wade and Professor Greenberg saw that, as Dr. Chavis shared how his research and community work transformed the people of Salisbury to acknowledge their legacy of lynching, the seminar students were inspired to consider what they, as future lawyers, might do to address racial terrorism.

Inspiration to take on the critical work ahead came to Albert Stancil ’22 while listening to Professor Chavis. “As law students, we’re the future of the legal profession and will eventually play a substantive role in how justice is perceived,” Stancil observes. “As lawyers, we’ll be in the position to create and interpret the law. So it’s imperative that we become more aware of previously unacknowledged social constraints and oppressive structures that are prevalent in minority communities and, with that awareness, consider how restorative justice could serve as the future of our justice system.”